What does it mean to be an artist? Where do artists draw inspiration? That’s what the producers of BRAVO’s Work of Art: The Next Great Artist, decided to ask the artist contestants in this week’s episode, “Child’s Play.”

For this week’s challenge, the artists were taken to the Children’s Museum of the Arts, and asked to create works of art that evoked the inception of their artistic expression. The artists could use only the kid-friendly materials available at the museum, including chalk, finger paints and crayons.

Asking an artist, or anyone else for that matter, to dig deep into the childhood memories vault and pull up possibly unanswered questions and unsolved conflicts is a difficult challenge. Above anything, it forces one to first be honest with the past, and then try and create something that embodies a larger meaning, and in turn communicates a message to others.

Jaclyn dove right into her “feelings of isolation,” which she has obviously not worked through. All of her work up until now has been about her body and the male gaze—how she outwardly appears to the world. Asking her to dig inside and pull something out resulted in an extremely weak piece that she cowardly named Untitled. Two paintings that look like cheap Rorshawk tests hang on the wall; a string with different colored pipe cleaners hanging off from it streches across the paintings. Blocked and deserted, Jaclyn resorted to abstractions of an idea that she couldn’t piece together.

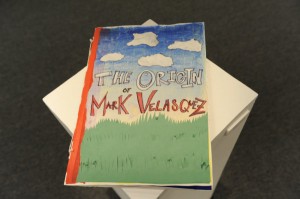

Mark was able to at least access childhood emotions in his little boyish comic book, aptly titled Origin Issue. On the front, Mark scrawls cartoonish letters that spell out “The Origin of Mark Velasquez.” Mark explains that he “never had art supplies growing up,” so he just used his mom’s office supplies like white-out and rubberbands. While honest, the piece is self-indulgent and hardly expresses nothing aside from the artist’s experience growing up poor which, on its own as a weak piece, hardly fosters much sympathy. Later Mark falters when identifying as an artist—he isn’t sure that’s what he really is, and this challenge makes that clear.

Cheerful Abdi struggles while trying to cope with and express his experience of being raised by a single mom whom he said “kept him on the straight track.” Abdi names his piece Straight Line, drawing cartoonish symbols and logos on separate pieces of white paper—a Nike SWOOSH logo, a star, bubble letters spelling out ABDI, a gun, a basketball—that he lines up in a grid on the wall. It’s impossible to glean any larger meaning from these because Abdi isn’t able to fully express what he is trying to communicate about the moment during childhood when he realized he was an artist. Instead, he just went back to being a child. But to Abdi’s credit, he doesn’t question that he is, in fact, an artist, which suggests that he has the confidence to make it to the next round.

As of this episode, Ryan has fulfilled pretty much all of the tortured, starving, intellectual artist stereotype by checking off a number of cliché boxes: he wears mostly black, he is heroin-chic thin, he chain smokes cigarettes, and he’s always “smelling of alcohol,” as told by the naïve, Jesus-loving Abdi in a previous episode. In this episode, however, he finally gets to the root of his issues, and shows that there’s more to him than anger and arrogance. Ryan starts off at the beginning of the episode by explaining that he really only has $24 in his checking account, and then realizes that since his insurance has gone through, his account is probably negative. Ryan tells how he was raised Jehovah’s Witness, but broke away from it as he matured. Then, in an emotionally wrought moment of near-breakdown, Ryan explains, while on the brink of tears: “My mom doesn’t respect my life choices, but she’s the reason I am an artist.” It is a moment of clarity, because for just a moment Ryan drops the hipster artist act and gets real. Sadly, the act comes right back up again, as Ryan creates another failed work of art. Ryan thinks that he can channel his childhood memories by drawing with his non-writing hand, but instead his work is just scribbles on paper posted to the wall, with boring images of his mom and dad underneath a rainbow. There’s a gold star pasted above the four jaggedly arranged drawings, and below Ryan throws his crumpled pieces of paper—failed attempts at making this work. When asked to explain the piece, he jumps right back into his cool guy image obsessions, explaining that he “carefully disheveled it—like I do to my own hair.”

A few episodes ago, Ryan made fun of Miles and Nicole for being a “match made in Urban Outfitters heaven.” Maybe Ryan should take a good long look at himself—he’s the one comparing his art to his cool haircut, and if that doesn’t qualify someone for Urban Outfitters heaven, I don’t know what does. The BRAVO producers saw that Ryan’s time was up, that his image wearing thin, and that’s why this had to be Ryan’s last week. Every shot of him outside of the studio is either of him drinking or smoking. His body is worn, and even Mark told him that he “looked drunk” even when he presumably was not. Yet for a moment, Ryan cracked open. But then he panicked and retracted, shoving his little twig legs back into his skinny jeans, and marching back down the street with his costume. He thought his childhood piece was deep, and that he was safe. As he exited the final critique, however, Ryan shoved his nose in the air, trying to feign confidence: “Now I can go back to making my realist oil paintings, and not worry about what anyone thinks.” For all the supposed growth Ryan made in this show, it’s a shame that he will probably go back to doing the same painfully unoriginal realist paintings that he has always done. But maybe that’s okay for Ryan—maybe that’s all his work is meant to be. But at least he has an MFA from Northwestern University—because that surely qualifies him as an artist.

For all the attention that the BRAVO producers have given Miles, I’m convinced that he was able to make it through this challenge only because of his strong character performance. In a total moment of defeat, Miles reverted to making a rudimentary first-year art school “conceptual” piece of trash, titled A Complete Roll of Duct Tape Over A 4’x6′ Plane, Accompanied by 3 Rubber Band Balls. Staggered black-and-white tiles arranged like an early 8-bit video game screen appear on top of a 4’x6’ plane. After getting frustrated with this empty piece, Miles made three rubberband balls, which he later lined up underneath the plane. Even Miles, the superstar favorite of the show, is questioning his identity as an artist: “I don’t consider myself not an artist,” he says, “but I’m not there yet.”

"A Complete Roll of Duct Tape Over a 4x6 Plane Accompanied by 3 Rubber Band Balls," Miles Mendenhall. Courtesy NBC Universal / Credit: Barbara Nitke

Peregrine and Nicole’s works emerged as the strongest in this challenge. Both women have kept out of the way of the drama of past episodes, holding their tongues, keeping their heads down, and sticking to their work. In this episode Mark notes Nicole and Miles’ flirtation, but other than that Nicole has gotten little attention. Peregrine has hardly had the camera on her, except in a few quiet moments where she gives meaningful insight into the struggles of others, like Jackie—who she noticed was really struggling this episode—and Judith, the obnoxious older woman who was booted off early on.

Nicole surfaces a childhood memory of her and her sister looking into the river, searching for salamanders. Hanging on a wall, the piece suggests that ghostly, creamy white feel of memory. A stack of nine off-white colored slabs with net in the middle hang by rope from a sturdy structure that’s nailed into the wall. Looking down from above, v gives viewers a feel of the sort of wonder these two young girls had as they gazed into a clear blue river, trying to catch a salamander as it wiggles by.

While Nicole’s piece proved to be strong, Peregrine won this challenge. Peregrine grew up in an experimental artist-hippie commune in San Francisco. Drugs, parties and sex were regular observations for her as a little girl. Many of her early drawings, even from childhood, were of “weird sex stuff,” as she describes it, suggesting a child trying to make sense of a world that was far beyond her realm of understanding. In the midst of this world of glitter parties, marijuana and needles, people would ask her to draw ponies, and so she would.

In her winning piece, Rainbow, Peregrine drew from this imagery of her childhood—a childhood that is unlike that of the other remaining contestants. She crafts a small unicorn with long white strings for hair, then places it in the middle of a pile of pink pills made from clay and paint, bottles with bits of glitter to signify heroin, cigarette butts with lipstick rings on them constructed from chalk and paint, and variously-colored candy and pink boa feathers. “AIDS hit San Francisco when I was young,” explains Peregrine during the final critique. Her work of art references that end of the party, when the gay men that she knew and loved as a child growing up in the Castro suddenly began dying of AIDS.

During the critique, Peregrine has a moment with judge Bill Powers, who nearly cries. Thinking of his own children, and how he longs to keep them safe and away from the dangers of the world, Bill’s heart opens up. Peregrine’s beautiful, sensitive piece recalls a childhood innocence lost in a San Francisco glitter life. Bill says that Peregrine’s piece work because she made the personal universal. Guest judge Will Cotton closes up the critique with a beautiful compliment to Peregrine: “I rarely see a work of art that I wish I had made myself, but that is how I feel about yours.” Because Peregrine dug down so deep into her personal childhood experiences, she was able to express something greater: The universal feel that parents have, of wanting to keep their child safe and out of harm’s way. Her piece shows a child stripped of her innocence at an early age. There’s no time to play My Little Ponies. This piece suggests the ways that children can carve out a little safe space for themselves by nestling deep into a beautiful, colorful world that is beyond the reality they live in. Peregrine’s Rainbow, beautiful and sad, ultimately suggests triumph. Peregrine closes the critique, her eyes big and deep blue, her body covered in her usual sparkly outfit, by offering up her piece as an homage: “The cool fun gay guys that I was friends with as a kid would be happy I won,” she says. “It gives me confidence that I can make it to the end.” And for just a moment, glitter covered the gallery.

It is important for artists to tell their stories, to remember that moment when they first knew. This week’s challenge separated the emotionally inept and insecure from the rest, demonstrating that without a strong foundation, it is impossible to move for one to move forward creatively.

wtf why is no one talking about how absolutely awful the challenges in this show are, and how absolutely revolting the work is? Hellll-OOOOO!!!!!!?!??!! this show is a total JOKE!!!!!!! DUH PEOPLE WAKE UP