By Alicia Eler & Patricia Herrmann

Pop culture is replete with stories of young men realizing their potential and becoming heroes. In the first season of Work of Art, pop culture’s introduction to the heretofore secretive Art World, America was provided with the familiar hero’s story.

In the tenth and final episode, The Big Show, the winner was decided and broadcast on national television to glowing screens across the country—a teenager in the Bronx, a get-together in rural Nebraska, a liberal hippie family in Berkeley. These different factions of America saw the Art World’s place in pop culture. Producer Sarah Jessica Parker wanted to prove that the Art World is no different from the rest of American pop culture. Abdi Farah, the artist who won the competition, was not the person who made the best work. Rather, he was the contestant that made the transformation of the mythical character that BRAVO wished to put forth—from unsure boy to superman.

Three artist-contestants remained. Their last names were not used. In the eyes of pop culture, they were still children. Abdi, Miles and Peregrine arrived at the Brooklyn Museum, where they were greeted by the judges and told that the winner of this next challenge would be awarded $100,000 and a solo show at the Brooklyn Museum. Then they were sent back to their hometowns to prepare a full solo exhibition that would decide the winner.

The three final contestants: Peregrine, Miles and Abdi on “Finale Episode”- Credit: David Giesbrecht/BRAVO

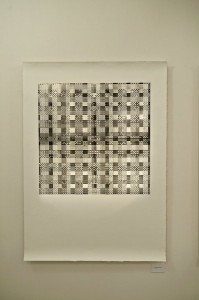

Miles went back to Minnesota. He used his iPhone to shoot pictures of a homeless person as captured on a White Castle surveillance camera. Later, he learned that this person froze to death. Miles multiplied and abstracted these simple, lo-tech images to a point of near-optical insanity, suggesting an obsession first with the homeless person, with death, and then with the visuals themselves. Like his work in Episode 9, Miles’ final show, And Two White Castles, That’s It, highlights the many ways he can see. But while beautiful to look at, this work became so abstract that its meaning was sometimes unclear. Miles’ work evolved throughout the series, and continued to do so in this final exhibition, but it did not win the competition.

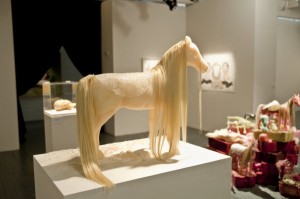

Peregrine’s final show, Fair Game, was a magical wonderland – both a child’s fantasy world and an illustration of adult hyper-excess. On a large sheet of paper, a Rococo frame rests between two boy heads, their cheeks rosy, their skin peach. They look out at the viewer, but do not make eye contact with anyone. More boy heads and more ponies, similar to the one from Peregrine’s Episode 7 piece, Rainbow, are draped on piles of red boxes stacked in the middle of the gallery. Gaudy wax Rococo picture frames lined one wall. Inside a glass box, on top of a pedestal, a wax sculpture of a beautiful boy head lies, its neck twisted awkwardly, gazing off into the sky. In a suite of drawings lining another wall, images of girls throwing up intensified the feeling of overconsumption already present throughout the gallery. The girls vomited different colors from their guts, and one even throws up on herself in the middle of a flower valley. Peregrine set up a cotton candy machine in the gallery itself, serving pink froth to the show’s visitors, heightening the transformation of the space.

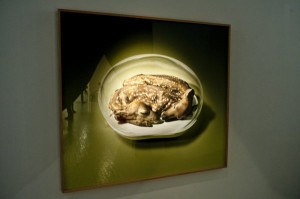

Anchoring this floating world was a large photograph of two unborn, twin baby fawns. The actual fawns, which usually live in Peregrine’s studio, have been her muse. In this show they symbolized a place between life and death – reality and unreality. Peregrine’s show bridged the child’s fantasy land and the harsh reality of adult excesses within a consumer culture based on evoking these fantasies. Both Peregrine and her final exhibition, Fair Game, embodied and revealed pop culture truths. However, Peregrine’s was not the transformation that won.

Television ultimately presented what America and pop culture want to see: the art student transforming into a “real artist” – the transformation from a nobody to a superhero. The winner of this show is not the person who made the best art, but rather the person who made the transformation into hero on-screen.

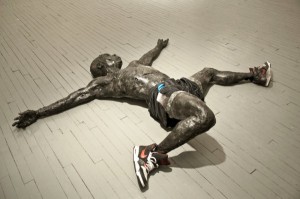

Abdi Farah, the 22-year-old artist who recently received his BFA, took home the prize. His final exhibition, Luminous Beings, presented his transformation through images of himself and other men. One muscular figure is stretched out on the floor with basketball shorts and Nike hightops; in one painting, a blue negative of what looks like Abdi hangs upside down. In yet another painting, a group of guys gathered, their backs to the viewer. Abdi demonstrated a strong ability for realist painting and sculpture, but more importantly he had visibly grown as an artist throughout the show. Even Jerry Saltz noticed.

Abdi won. And he won not because he was a better artist, but because he transformed on the screen, as Peregrine says during this interview with ARTINFO.

“I’m really happy for Abdi. He’s an amazing young man. And he truly had the hero’s journey. He became his own hero,which is a really hard thing to do. Most people are lucky if they get a good photograph taken of them in their lives, but Abdi managed to wrestle and conquer his own shadow in front of a million people. So I’m happy for him for that.”

Miles and Peregrine are adults, but they are not heroes. They cannot win the competition, but they cannot lose it, either. They win in other ways—more visibility in the Art World, growth first as human beings, then as artist and last as reality TV show characters. But they do not qualify as winners of a reality television show that crowns only one person “America’s Next Great Artist.” Their work is not that of a freshly minted pop culture hero. They had already transformed before they got to Work of Art. They were not concerned with wrestling their own shadows. They did not struggle to become.

Abdi made the transformation from child to adult, from art student to artist. His win made for a complete hero’s journey, and a nice work of art for BRAVO.