TMI (Too Much Information)

Kathy Halper

Packer Schopf Gallery

May 24 – July 6 2013

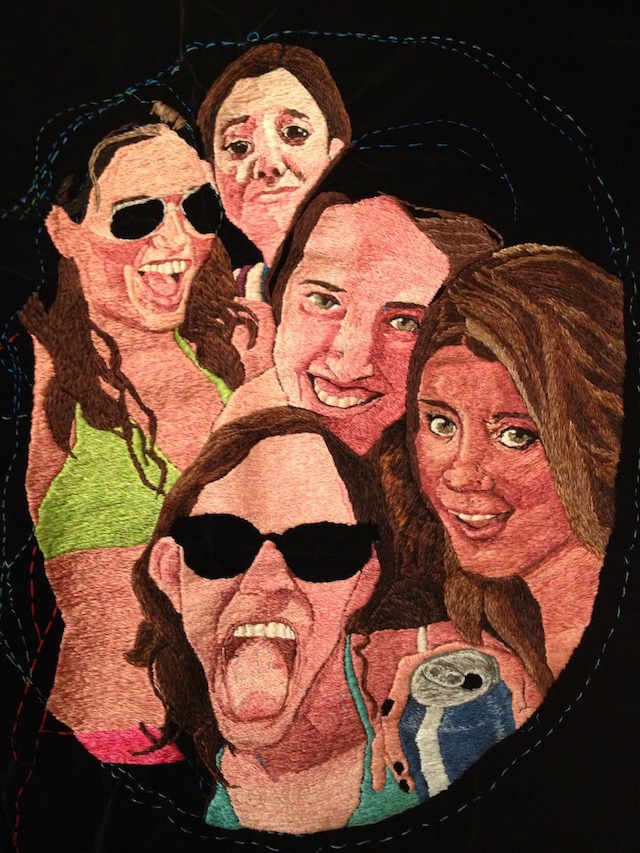

It is that moment at the school prom when the hot football player flicks off the camera before he gets wasted, and then falls between his high school sweetheart’s legs for the first time. The freshly pricked former virgin, sitting in her parents’ living room the next day completely hungover, reaches into her purse and uncovers a bag of Oreos labeled “EMERGENCY.” She wonders: How did those get there? Then she posts that question to Facebook. Semi-private moments that were once meant for a few select sets of eyes are now public and online for the person’s social network audience. From parents who happen across teenagers’ Facebook news feeds to real-life friends given access to this information to Internet trolls jonesing to bite off another reddit comment thread, these are the types of visual and auditory vulnerabilities that spread fast on the social web, giving those privy the opportunity to react, respond or simply ignore. But SRSLY, who doesn’t want to talk about what’s on their mind today?

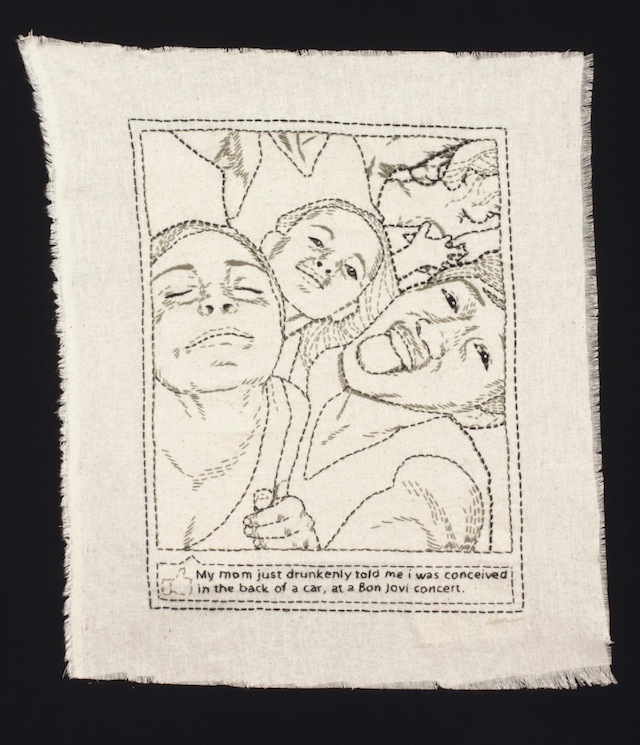

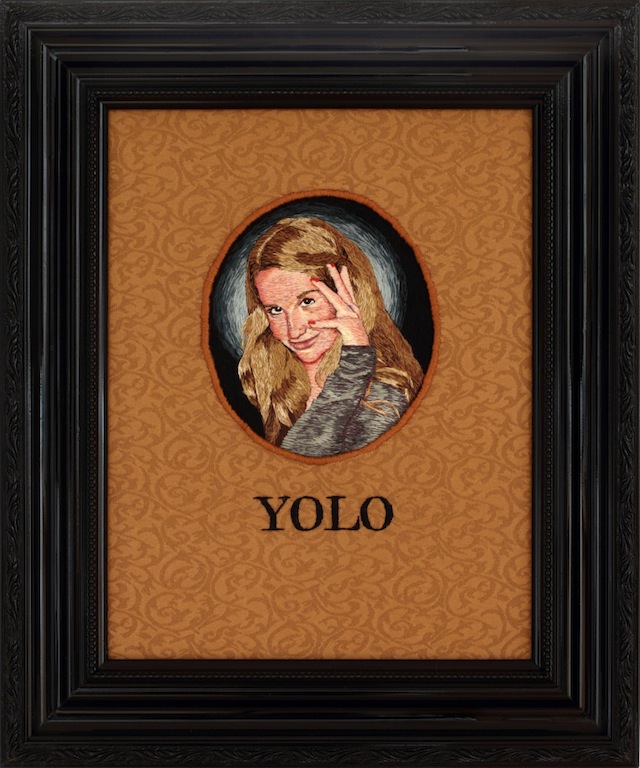

Kathy Halper’s work mirrors adults’ ongoing fascination with youth culture, imbuing it with today’s hyper-social-networked edge. Media theorist Marshall McLuhan predicted the advent of the Internet, suggesting the future of living in a global village that acts and reacts to the pulse of culture. He notes that it is not adults, but rather youth that instinctively and intuitively understand this type of “electronic drama.” This is where Halper’s work begins. Creating embroidered drawings from photographs of adolescents that she finds on social networking sites, Halper’s work questions the disappearing space between public and private online, the subversive use of fabric, needle and thread, and the role that technology plays in shaping adolescence. Her work questions the ways we look and observe, and how adults connect with the youth of today. These questions stem from both her personal experience as a parent, a love of the homemade craft, and an awkward relationship with the Internet.

The artist’s decision to use embroidery rather than painting is paramount. For her, reclaiming this supposed “women’s work” is a radical act, resulting in an empowering, labor-intensive product made by a woman who is also a mother. Much in line with women who have embroidered before her—from the Victorian era onward until today—Halper’s decision to use embroidery rather than painting or photography, provides commentary on the role of women in society today. Her work continues the dialogue around the ever-evolving construction of femininity that “contains its own curious power,” as Rozsika Parker writes in The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. “The stereotype of embroidery as a vain and frivolous occupation, like the stereotype of the silent, seductive needlewoman, controls and undermines the power and pleasure women have found in embroidery, representing it to us negatively.” Additionally, embroidery is a practice specifically attached to mothers and daughters—and as Halper’s daughter appears on occasion in her social media-inspired embroideries, the familial connection is strengthened or, as it were, sewn into the fabric as skin tones, memory, relationships, and perhaps drops of blood that bleed onto the fabric as she furiously sews.

Painting these images would be too easy, though certainly time-consuming. By choosing embroidery rather than paint these of-the-moment images that pop up on social networks, Halper calls into question time as we experience it online. Halper’s work flips the fast-paced social space, where decisions are made faster than synapses spark, to a meditative, labor-heavy cloth canvas where subversion and empowerment are threaded. In an age of instant gratification—shopping online, liking and sharing quickly and without further thought—Halper’s embroideries stand in deft opposition to the mediums from which they appropriate their images, daring to stand the test of time.

Halper’s fascination with youth culture isn’t a result of the social networked era. Joseph Sterling photographed adolescents in the 1950s and 1960s, shortly after the term was first invented. Indeed, before this post-World War II era, the idea of “teenager” as we know it did not exist. Halper’s work literally needles in our culture’s continued fixation on and commodification of teens and tweens. And much in line with Marshall McLuhan’s thesis that, thanks to social networks we are all becoming one global village again, Halper’s discovery of teenagers in their online sanctuaries happened serendipitously after her kids’ friends friended her—and presumably other mothers—on Facebook, the world’s largest social network. Photographs of what happened last weekend, or even just last night, are readily available and even freely offered by teenagers for their entire network to see.

This type of easy access is both a parent’s dream come true and their worst nightmare simultaneously. But is it really teenagers’ fault? Blame it on the medium. Authenticity lies in Halper’s embroideries of fleeting adolescent moments, and are readily depicted through a medium that mother knows best.

—Alicia Eler

Chicago, Illinois

April 2013