From Artsy Magazine, October 13, 2015, by Alicia Eler:

Portrait of Steve Martin by Danny Clinch.

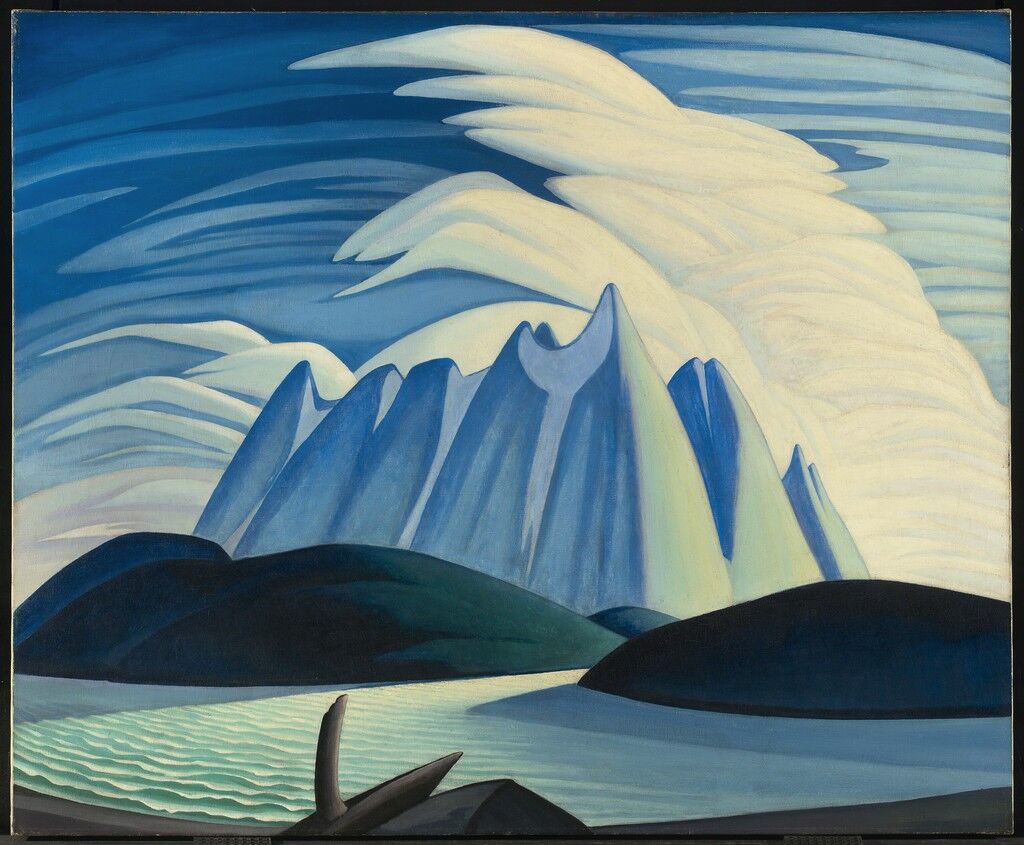

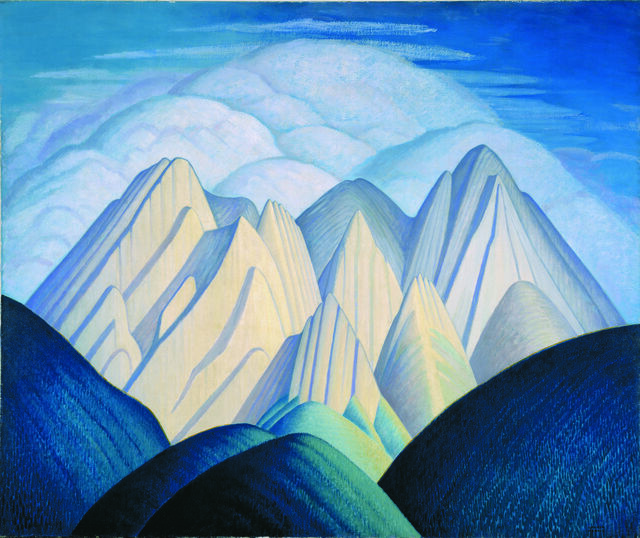

While he’s no stranger to the art world, legendary comedian Steve Martin has only just cut his teeth as a museum curator. His first foray into the field is “The Idea of North: The Paintings of Lawren Harris,” a survey of the late painter’s work from the 1920s and ’30s at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Organized together with Cindy Burlingham of the Hammer and Andrew Hunter of the Art Gallery of Ontario, which collaborated on the show, it is the first major exhibition of Harris’s work in the U.S. A member of the renowned Group of Seven—an association of painters devoted to capturing the Canadian landscape—Harris created dreamlike, abstracted images in cool, lucid palettes of blues and greens, offering fresh, beaming visions of the Canadian wilderness. The works on view in the exhibition (which omits those in Martin’s own collection of art by Harris) refer to three particular locales: the North Shore of Lake Superior, which Harris painted between 1921 and ‘28; the Rocky Mountains; and the eastern Arctic, inspired by a trip there in the 1930s.

Alicia Eler sat down with Martin at the Hammer to talk about his longtime love of art, his own collection, and his experience curating this show of Harris’s work—which was three years in the making.

Alicia Eler: When did you first become interested in art?

Steve Martin: I first became interested in art just out of high school and into college. A friend of mine was an artist, and he was a well-spoken and enthusiastic person. And that would have been about 1964, a big year in the art world. We had just come through the Abstract Expressionists and Jackson Pollock and de Kooning, and then the word about Pop started to spread. So you had these two completely opposite styles creating a lot of energy in the art world, and it was very, very exciting. But I got interested in 19th-century art first, and eventually to more modern art. I have many friends in the art world who are some of my closest friends.

How did you learn about art? Through going to shows and museums, or did you take classes?

No, it was all autodidactic. I was just obsessed. When I would tour around the country as an unknown comedian, I always spent the day going to college art libraries. And then I—I don’t know if “amassed” is the right word—a big collection of art books and monographs, which I thought was very important to have.

Was art a nice counterpart to performing?

It was a great counterpart to being a celebrity because you had this place to go where you weren’t a celebrity, where the artist was the celebrity, and where people loved to talk about art. I wrote about that in my catalog essay for the show—that co-curators Cindy Burlingham and Andrew Hunter and I would drive around and prove my point that art lovers can talk about art all day long and nothing else.

That’s true of art people. When did you start collecting art?

When I was 21. I bought some little 19th-century landscapes and an Ed Ruscha print of the Hollywood sign. That’s where I started.

Do you have a strategy for collecting?

No, no. I’ve had a strategy in the past—of having the collection be very coherent. Like, say you are collecting Abstract Expressionists, you want to get every one of them including Adolf Gottlieb and the lesser-known names. Or if you’re collecting 19th–century American Hudson River painting and you try to get a good sampling of the important people—Sanford Robinson Gifford and Jasper Francis Cropsey and Thomas Cole, etc. But I found it required me to get a picture I didn’t really love that much, because you’re trying to get the name. And eventually I just got pictures I really, really liked.

How is it possible that Lawren Harris is a totally unknown artist in the U.S.? I think that’s quite sad.

Well, I don’t think it’s sad. I think that’s just the way things are, and it does take a while for artists to become known. I’ve read that Vermeer—I’m just remembering this—that Vermeer was not Vermeer until the late 19th century or early 20th century when he started to be discovered. It takes time to discover and absorb all of the artists that exist and bring them into your consciousness.

Was there something that drew you to this period of his painting from the 1920s to the early ’30s?

Well there’s a unity to this period. Even though he’s painting essentially three different locations, his style is very unified, and the locations allow him to paint drama, to paint serenity, to paint symbolically. I think that’s why I really focused on this period.

Looking at these paintings online, I kept thinking about Ansel Adams’s photographs of the American wilderness when it was more of a place to explore. I think of Adams as an explorer. Is that the case with Harris?

I don’t think of Harris as an explorer. He was a hiker, but he wasn’t exploring the Canadian North. I think he was just looking for subject matter, and there was a huge shift at this time, around 1921. He was painting street scenes, strolling couples, in sort of an impressionist mode, and then there was this big change for him. When he took the people out, and he took the organic material out, that’s when the pictures came to life. That’s when they started to mean something.

Why do you think that is?

My friend Adam Gopnik said that he took out the narrative. When you have people in the picture, you also have a narrative. What are they doing? Where are they going? When you take them out, you have the opportunity to make a symbolic landscape.

Have you spent much time in the Canadian North?

No. Well, I shot a movie in the Yukon, and it was like living in a Lawren Harris painting.

There seems to be more of a complete openness that I don’t feel is portrayed as much in the American West. Do you get that sense much from the Canadian North at all?

Not in Lawren Harris. I think he’s making paintings rather than depicting the landscape. He was trying to make great art, not great photographs.

—Alicia Eler